Eating Habits III - More variety, more obesity...

A typical presentation of foods one might see at an all you can eat buffet.

"A varied diet of everything in moderation". Classic advice; we have seen why moderation may make things difficult for us to stay lean. But surely a varied diet is good advice?

While eating a wide variety of foods means we are likely to satisfy our nutritional needs, it has a very important flip side; the more food we encounter, the more we eat...the more we eat the mo.......(one can guess the rest).

The implications of being presented with such vast variety bring us to one of the most fundamental properties of our nervous systems - Habituation. Habituation is one of the simplest forms of learning - the more we are exposed to something, the more habituated we become, the less we respond. When a stimulus is new, we are very interested in it as it might be important, over repeated exposures, it becomes much less important and we stop paying attention.1

“HABITUATION

A form of learning in which an organism decreases or ceases its responses after repeated presentations”

Recall from the previous article that hunger is an 'output' of the brain, not an input from the stomach. The process of (disarming) habituation plays a key role in tricking our nervous system and explains why a great many of us don't actually eat due to hunger, we eat on our emotions and whats influencing us. Optical illusions are a simple way to demonstrate how easy it is to trick another of our nervous system functions - vision.

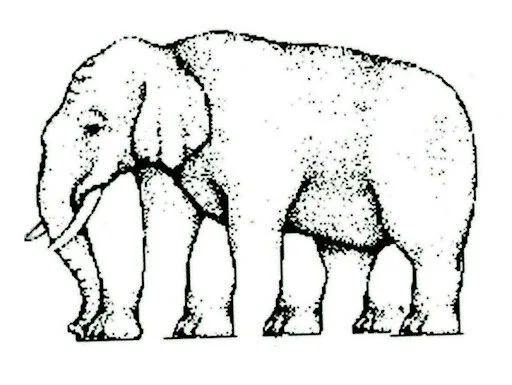

How many legs does this elephant have?

If the image we receive with our eyes does not match our expectation of what our brains think we 'should' see then it creates an 'optical illusion'. Optical illusions demonstrate how easy it is to 'trick' our nervous system and shows vision to be an 'output' of the brain, not merely an input from the eyes as many may believe.

Satiety is the term used to describe feeling full. How simple life would be if we felt full, or satiated when we had met our nutritional requirements. Or perhaps we do feel full, yet for some reason we can (and do) continue eating??

A direct quote taken from Guyenet (2017), P.62:2

In a pioneering 1981 study by Barbara Rolls and colleagues, volunteers rated the palatability of eight different foods by tasting a small amount of each, and then were provided one of the foods for lunch. After lunch, they once again rated the palatability of the same eight foods by tasting them. Rolls found that the palatability rating of the food the volunteers had eaten for lunch decreased much more than the palatability rating of the seven foods they hadn't eaten.

When the volunteers were presented with an unexpected second course containing all eight foods, they tended to eat LESS of the food they ate for lunch. This shows that we can eat our fill of a specific food and feel totally satisfied, but that doesn't mean we won't eat other foods if they are available."

“The Buffet Effect

We do not get the chance to habituate as every few bites is new sensory experience”

What this clever landmark study showed was that we get full or satiated if we have the same food - a term called sensory specific satiety. This phenomenon is what explains why we can always find room for dessert after we eat ourselves full and why when presented with enormous variety at a buffet, we overeat, every time. Researchers call it the buffet effect. At a buffet we do not get the chance to habituate as every few bites is a new sensory experience.

It is clear to see that the context and the pursuit to be entertained by ones food both play a great role in our desire to eat and significantly influence whether or not we feel hungry.

Researchers way back in 1965 wanted to take these influential triggers out and see what effect this had on weight loss and more importantly, hunger3. Volunteers were given access to a machine that dispensed a liquid through a straw. They were allowed as much as they wanted, but nothing else (this was carried out in a hospital so they could be sure no other food was eaten).

The liquid was bland, completely lacking variety and other environmental food cues, but met their nutritional needs.

“Morbidly obese volunteers lost half their body weight in 185 days and did not feel hungry once”

When researchers fed two lean people for up to sixteen days; they intuitively consumed their daily calorie requirements and maintained their weight. Next, the researchers repeated the experiment on two morbidly obese volunteers weighing near four hundred pounds (180kg / 28.5 stone).

During the eighteen days observations the volunteers ate a meagre ten per cent of their normal calories and predictably lost lots of weight (approx. 23 pounds). The researchers sent these volunteers home with the formula and advised them to continue indefinitely. Over the course of 185 days the volunteers lost nearly half their body weight.

An abundance of food was historically constrained to the rich (who were much more likely to be obese than the poor). Modern society has it that food abundance (and obesity) transcends the hierarchy - Drewnowski (2009).

This is not surprising if they were under eating daily by as much as ninety per cent (and ultimately unsustainable once weight loss plateaus'). However the remarkable finding was that the volunteers were not feeling hungry at any point during the study.

Similarly impressive results were achieved by Chris Voigt, director of the Washington State Potato Commission who for reasons not relevant here, ate twenty potatoes a day (only) for sixty days. Twenty-one pounds melted off (amongst improvement in a plethora of positive health measures) and again he did not feel hungry at all. You can read his story here.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Is eating a varied diet bad for you? Absolutely not. Our ancestors would have given anything to experience the variety we do today. That variety however is almost certainly one reason we fight so hard against our waistlines. The ever varying taste sensation and foods prevent us habituating to them and trick our perception of satiety.

“Do you live to eat? Or do you eat to live...”

One of the features of modern day hunter gatherers, or those who live in the blue zones is that they eat what they produce which at any given time, would be no more than 5-10 foods, rotating with the season.

Anecdotally, one of the features of athletes is repetition of very simple foods. Many people will say that they couldn't handle eating the same foods over and over. This makes total sense when we look at how our brains enjoy novel new experiences, we get great reward from eating and we often crave being entertained by what we eat.

We often admire athletes as they are very lean and we know people in the blue zones and our ancestors were lean from careful metabolic studies4. Enjoying an abundance of food and variety is perhaps a very twenty-first century issue. Simplifying everything back down and into a framework could be one of the keys to replicating the physiques of those we admire. We also know that simplifying things will also make you feel less hungry.

Do you live to eat?

Or do you eat to live?

Understanding that we all have a constant play off between our chimp and human brains and the issues surrounding moderation and variety is one thing. In the next article we will look at highly rewarding foods and why they draw us back for more, a lesson learned in Vegas and how anticipation can actually work for us and not just against us.

Luke R. Davies :)

REFERENCES

- Guyenet, S. J. (2017). The Hungry Brain: Outsmarting the Instincts that Make us Overeat, Vermilion, Ebury Publishing, London, UK.

- Rolls, B. J., Rolls E. T., Rowe, E. A. and Sweeney, K. (1981). Sensory Specific Satiety in Man, Physiology and Behaviour, 31(1), P.137-42.

- Hashim, S. A. and Van Itallie, T. B. (1965), Studies in Normal and Obese Subjects with a Monitored Food Dispensing Device, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 131(2), P. 654-61.

- Pontzer, H., Raichlen, D. A., Wood, B. M., Mabulla, A. Z. P., Racette, S. B. and Marlowe, F. W. (2012). Hunter-Gatherer Energetics and Human Obesity, PLUS ONE, 7. (Cited in REF 1 - P.96)

- Drewnowski, A. (2009). Obesity, Diets and Social Inequalities, Nutrition Reviews, 67(1), P.36-39.